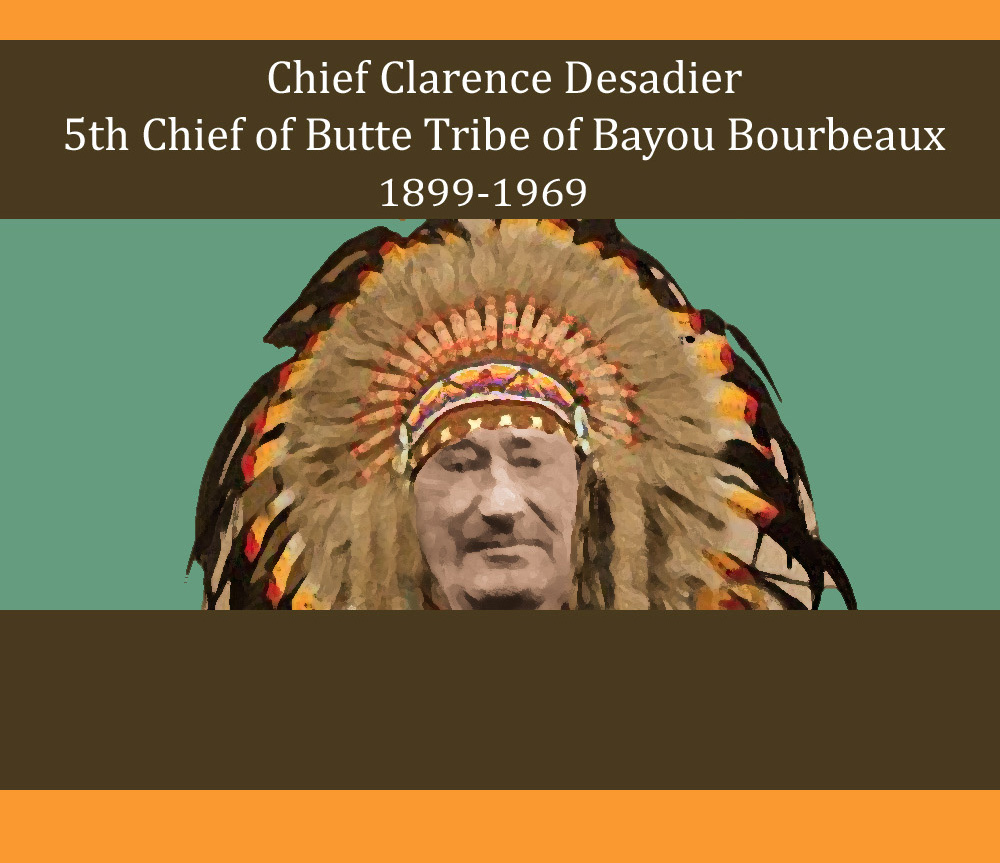

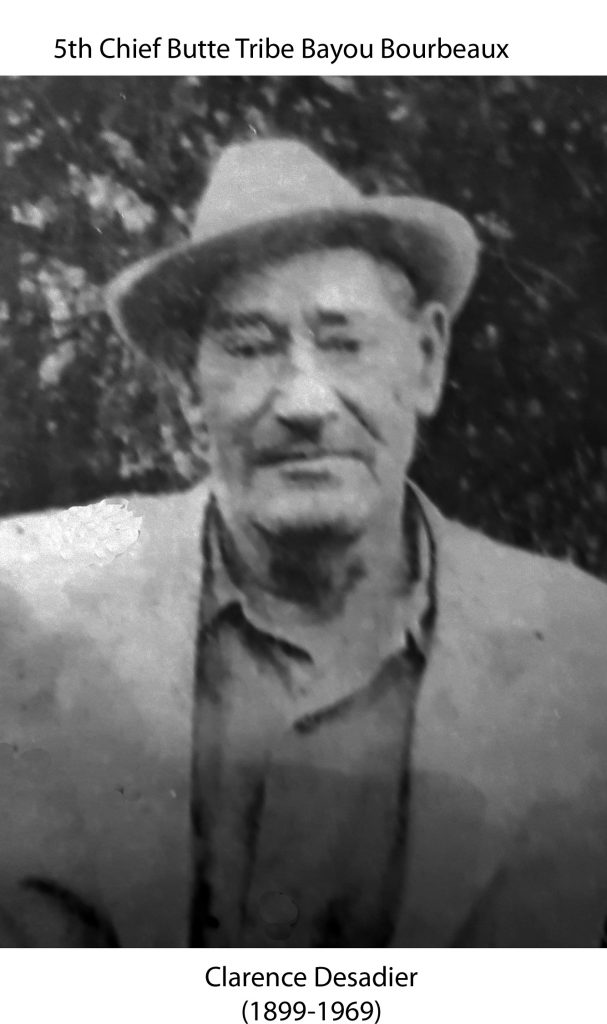

Chief#5- Clarence Desadier (1899-1969)

Clarence Desadier was the second son of Felix and Victorine “Fee” Flores Desadier. Although he was the second son, he was chosen by his parents for the position of the fifth family leader/chief of the Butte Tribe. He was chosen for this position because of his obvious love of family, work ethics and his ability of keeping the family together. As a businessman, his skills in managing money and real estate were outstanding. His parents could depend on him to do whatever it took to see that the family did not go lacking in food, shelter and education. Not only did he care for his family, his love for his entire bayou community was evident by the way he shared what he had with others.

In true Native American cultural, familial lifestyle, Clarence Desadier found his wife and life partner within his tribe. On November 17, 1917, Clarence married Louella Waters, his second cousin. Clarence and Louella’s grandmothers were sisters, Seraphine Josephine and Marie Zelina Larenaudiere. The Larenaudiere sisters were the second-great granddaughters of Marie Theresa De La Grande Terre, the Chitimacha wife of Frenchman Jacques (dit Nantes) Guedon. Together, Clarence and Louella raised three sons and four daughters on the same land that the present-day chief, Rodger Collum, resides.

Clarence’s service to the family began in the early 1920s when his father’s health began to decline. Following Felix Desadier’s death in 1926, Clarence became the head of the family with his mother, Fee, standing at his side. Concerned about his people, Clarence aka “Parrain” to the family, made sure that his truck garden was planted and his milk cows were well cared for and ready to produce milk for the family as well as those in the community who were living in hard times.

Undoubtedly, the late 1920s and 1930s were hard times for those raising families in and around Bayou Bourbeaux as well as the entire United States. 1927 brought the historic Mississippi River flood. The flood waters in Louisiana displaced many of the Butte Tribe families who had relocated their families closer to the Mississippi River in hopes of making a better life for their families. October 1929 marked the month of the Wallstreet Crash and the onset of the Great Depression. Then, shortly after the economy finally began to recover in 1939, World War II began and the young men within the family received draft cards that stripped them away from their families to serve their country on foreign shores. Clarence had two sons, Otis and Henry, who served during WWII. During these hard times, Clarence made sure that those in his family who remained on Butte land had jobs to go to, food on the table, beds to sleep in and roofs over their heads.

Through it all, Clarence was careful to keep the family bloodline under-the-radar. Why? His grandfather, Joseph Desadier Jr., lived through the 1830s Indian Removal Act. Joseph knew only too well the discrimination, hatred and disrespect that the United States government held for the indigenous people of America. Joseph made the decision during those times that the “tribe” would become a “family.” No longer would the Butte Tribe acknowledge their Native American bloodlines. White settlers were determined to claim the rich, alluvial lands of the Native Americans. While on behalf of the settlers and their own interest, the government with no concern for Native Americans forcibly removed indigenous people from their ancestral homes to ghost lands of the West with no resemblance to the land of their forefathers. To keep Butte lands and families in place, it was necessary to take on a new cultural identity.

Clarence’s mother, Fee, lived to be 108 years old. At her death, all of her assets were left to Clarence to distribute. Fee trusted her son to do what was right with her belongings. His decision on distribution of her property was based on work ethics of his siblings. Clarence carried on the expected duties of the family leader and continued to oversee family business meetings and reunions. He kept the family tightly knitted by working together, growing crops together, burying their dead together, and so forth. He was a well-respected leader who held many titles. He was the local game warden, a deputy sheriff, a preacher, as well as a farmer and cattle man.

Clarence’s main concern as a game warden was outsiders hunting on Butte lands and killing wildlife need to support the welfare of his people. This concern was what actually led him to become a game warden. Times were very hard and the family depended on wildlife such as deer, hogs, rabbits, squirrels, ducks, geese and other game to survive. As an official federal wildlife game warden, he was responsible for the preservation of wildlife on Bayou Bourbeaux, which in turn allowed for the survival of this family. To illustrate this point by comparing/contrasting hunting rabbits on the bayou in Clarence’s lifetime compared to hunting rabbits on the bayou in today’s world, taking a ride down the backroads of the bayou at night time to see how many rabbits can be spotlighted would tell the tale. During the lifetime of Clarence, it was easy to spotlight hundreds if not thousands of rabbits running across dirt roads and fields at night. In contrast, today, one can ride for miles and miles up and down bayou roads and not see one rabbit on the side of or crossing the road.

Spirituality/religion has always been a significant factor in the lives of the Butte families. For Clarence, this was certainly true. Throughout his lifetime, he along with his parents, played key roles in the building of the Christian Harmony Baptist Church in the Pace Community. The land that the church and parsonage sit on today was donated by Felix, Fee and Clarence Desadier. History of that little church began in the early 1900s with both Felix and Clarence as well as many other family members having served as deacons throughout its lifespan. Hundreds of family members were born (christened), baptized and buried into that church. The church recently celebrated its 130th birthday celebration.

Saturdays and Sundays were always times for family gatherings. Grandma Fee, Clarence’s mother, always lived within walking distance of her son’s home. Her children were raised to understand the importance of family togetherness. Saturdays were visiting days. Family from near and far would travel to sit around the yard under trees and on the porch to watch children play, drink coffee or sweet tea, enjoy fresh baked tea-cakes, talk about current events and relate oral family history. Saturday gatherings were no less than 20 to 30 family members passing by. When the evening came, someone would likely break out a fiddle and it was time for music and dance.

Sundays were always spent in church, no exception. Everyone would bring pot-luck dishes and there was always more than enough food to share with all who attended. At times, upward of 100 people would come to “Paw” Clarence and “Maw” Louella’s house to eat. The norm would be 50-60 people after church for lunch. Family came from all directions. There was a pecking order to seating at meals. Elders were seated and served first followed by the rest of the family. Teaching children to respect their elders was and continues to be a major responsibility passed on by adults of the Butte Tribe.

Comically, Chief Collum likes to remind his people how special he was to the elders, or at least to his mom, Olla Mae, and Maw Louella. On Sunday just for him, they always made his favorite banana pudding (without bananas.) Knowing that Rodger had to wait in line with the children, Olla Mae and Louella had a special place set aside for him where there was always a bowl of pudding waiting just for him.

Each month, Clarence would call a meeting of family elders. These meetings were rather traditional in their schedule. About 20 elders would be in attendance. Clarence always opened the meeting with prayer. Coffee, tea, Kool-Aid, and teacakes were served. After taking time to greet everyone, the group would then sing old family, tribal songs. Money would be collected for family needs. There may have been family that were sick or short on cash to pay bills and the money collected would go to help with those issues. Storytellers would tell stories about life when they were children. They would relate to Rodger the traditions and customs of their lifetime. The elders would talk about the importance of hunting and fishing on Bayou Bourbeaux. Many within the tribe were hunting and fishing guides in Natchitoches Parish which was a popular tourist site for hunters through the state. Without the plentiful supply of wildlife, the family would have never made it through the hard times of the Great Depression in the 1930s. For Clarence and the elders, controlling and protecting Butte lands depended on keeping outsiders away from their land.

Fond, humorous memories of Clarence and Louella Desadier told by their grandchildren are numerous. Clarence’s children all lived in the surrounding area. Each evening, Louella and he would take a ride around to check on his daughters and their families before they went to bed. All the family knew that Maw Louella liked her beer, especially when she went riding. This created an issue for Paw Clarence since he was a preacher man. Rodger and his cousin, Buddy Hayes, laugh when they tell the story about riding with their grandparents at those times. Clarence would drive up to the local “beer” stop and park in the dark. Someone from inside would walk outside with a brown paper bag with Maw Louella’s favorite drink inside. Clarence would pay for it and they would be on their way.

Rodger always speaks of Maw Louella with a smile on his face. He would go to her first, whenever he wanted something that he felt his Paw or parents would deny him. Maw was always up to the challenge of making deals with him. He and his cousin-in-crime, Buddy Hayes, loved to go hunting beginning when they were only five and six years of age. Others may have objected but with Maw on their sides they pretty much knew, without a doubt, it was a done-deal. They had guns but ammo was hard to come by. Maw Louella always liked to cook rabbit. Maw would get the boys shells if they would hunt rabbits and bring her some back for supper. Now, you might think what was the big deal about getting shells? The big deal was that Paw Clarence was a Wildlife and Fisheries Agent. The boys were too young to hunt on their own and would have to go hunting behind their grandfather’s back. Paw confronted Louella. Louella in her slow, southern drawl would respond, “Now, Clar…ence, you know you enjoy eatin’ them rabbits.” That was it! No more was said about the boys hunting or Louella passing out the shells. Louella always had the say-so when it came to the pots and pans.

Buddy told the story that on a cold winter day Maw decided that she was going to cook geese for the family. The boys were around the ages of eight and nine at the time. She gave Rodger and Buddy a box of shells with the initial “HV” on them. What were they to do? If Maw said do it, they had no choice. So, they eagerly headed out with the dogs to the bayou waters to find the biggest, bad’est, fattest goose to deck Maw’s Sunday table. Suddenly, Buddy spied a gigantic goose that seemed hundreds of yards away. He pointed it out to Rodger and said, “We’re too far away for you to hit it.” Rodger said, “No, man! Give me one of those HIGH VOLTAGE shells Maw got us.” Buddy gave him the shell and, sure enough, that goose was as good as cooked. Rodger killed it on the spot. Buddy said, “Wow, Rodger! Never heard of those HIGH VOLTAGE shells. Maw needs to get us a bunch of them.”

On a more serious note, there were times that Clarence, as head of the family, had to shut the bayou down. Friday, December 6, 1957, Kenneth Wayne Frederick, Clarence’s grandson, left Clarence’s house with two dogs to go rabbit hunting. When the dogs returned without the grandson, Clarence called in the family, shut down the bayou and the hunt was on. The Town Talk newspaper of Alexandria, Louisiana, reported that, “It was the grandfather who traced the boy’s footprints from near the Pikes home for about 2,000 feet until they faded out into the swamp.” Bayou Bourbeaux was shut down for approximately two weeks. No one could enter or leave the bayou unless they were family or part of the search party until the body of Clarence’s grandson was found. The body was found partially submerged in the bayou under a Bayou Bourbeaux bridge near the Clarence community on December 18th, 1957. The coroner later ruled that the cause of death was drowning.

Years before that accident, another Bayou Bourbeaux crisis occurred when a tornado came through the bayou. A midwife who lived on the bayou was standing in her front yard holding her baby. The baby was not old enough to sit up by itself at the time. Suddenly, a big wind sucked the baby from the mother’s arms. The mother was in a panic running from one place to another to try to find her baby. She could not find her anywhere. Knowing that when people had problems on the bayou that Clarence was the person to contact, she immediately got in touch with him. Clarence formed a search party right away. For two days the community searched for that baby. On the second day, someone heard a strange sound coming from the field behind the Christian Harmony Baptist Church. It sounded like a small animal that was in trouble. Sure enough, it was the baby. He was alive and well. There are many more stories like these to tell. Much more than time will allow. Through good times or bad, Clarence never failed his people. His wisdom and love for his people were passed down to his chosen successor, Chief Rodger Collum.

Clarence and Louella lived their lives during the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. For them, they enjoyed all of the new modernized inventions. It would be accurate to say that in the Bayou Bourbeaux area they enjoyed the first of all that the new inventions that technology had to offer. They were first to have a phone, a tractor, as well as a car with an air conditioner and automatic transmission. They were also the first to purchase a television.

The passing of Clarence and Louella Desadier was mourned by many of the Bayou Bourbeaux community. At the time of Clarence’s passing in 1969, Louella stood by the side of her grandson, Rodger Collum, until he came of age to take on the responsibility of leading the family/tribe for the next generations. Louella passed that baton to Rodger at the birth of his first child and son, Shannon, in 1975.

Next article, 4th Chief of the Butte Tribe of Bayou Bourbeaux, Adolph Felix Desadier.